The Bury St Edmunds Magna Carta Pageant 1959

In 1959, over 50 years after Bury St Edmunds had staged its first historical pageant, the people of the town again caught ‘pageant fever’. Pulling together, they produced what was undoubtedly one of the largest and most successful historical re-enactments of the postwar period: the Bury St. Edmunds Magna Carta Pageant. It shared many of the themes of its 1907 older brother, by focusing upon Edmund, King John, and the Magna Carta. But it extended the chronology well beyond the original's finale of 1578 - all the way up to the present day - and also modernised the production for the new age of television. Historical pageantry had clearly come a long way since Sherborne, Dorset, in 1905. Aspects of Louis Napoleon Parker’s Edwardian vision remained, but they were now embellished under bright lights and amplified sound, with added humour and allegory. Even if it did not capture the nationwide publicity of the 1907 spectacular, the Magna Carta Pageant was still impressive in other respects- not least in how it managed to draw representatives from all over the Commonwealth, and a cast of 1000 local people. The appeal of a popular shared history had certainly not diminished in the little town of Bury St Edmunds, and neither had the enthusiasm for a proper knees-up celebration. For two weeks the town was en fête, with civic processions, luncheons, civic sermons, and decorated streets to go alongside the twelve pageant performances. When all was said and done, the Borough Council made a profit and could rightly claim a great success: a return to spectacular pageantry in Suffolk.

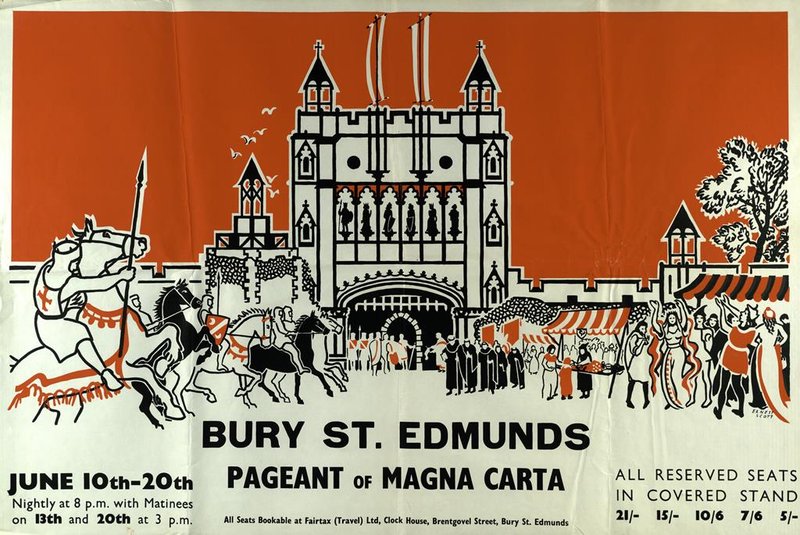

Poster advertising the Bury St Edmunds Pageant of

Magna Carta, 1959. By kind permission of the Suffolk Record Office, Bury

St Edmunds branch, BRO_EE500_32_3.

Mayor FG Banks claimed responsibility for coming up with the idea for a new pageant, after he was inspired by a much smaller event in May 1957: the Pageant of St Edmund. Presented by 70 young members of the St. Edmund’s Guild, the play had been written by Canon Richard Tydeman. After catching Banks's attention, Tydeman was quickly snapped up to write the script for the Magna Carta pageant. He was a local man, born at Stowmarket, Suffolk, and had been the vicar of All Saints, Newmarket, as well as rural dean in the same parish from 1954. In the year of the pageant, he was appointed an honorary canon of St. Edmundsbury. He was also an author, having published over thirty plays, many of which were performed both at Suffolk Drama festivals and further afield. He had also authored a televised play, as well as several Dramatic Interludes for the Religious Services for Schools (arranged through the BBC). His experience in pageantry was still building; the only scripts he had written were for the Woodbridge Coronation pageant in 1953, and the Pageant of St. Edmund that had so enthralled Banks. But his plays did enjoy a widespread popularity and, according to the Bury Free Press, since 1955 ‘not a single day’ had passed where one of his plays wasn't produced in some part of Britain.

With Tydeman on board, and the full support of the Borough Council, the next step was to find a pageant-master. The organisers managed to secure the talents of Christopher Ede: Britain’s leading and most experienced pageant producer of the postwar years. He was paid £1000 with £250 expenses - about £20,000 in today’s money (and about ten percent of the pageants total cost!). Ede had many large and successful pageants under his belt. Over 20 years previous he had helped produce the Pageant of Parliament (1934) and the Pageant of Surrey (1937). Before the outbreak of the war he widened his experience by moving into films, theatre and revue before, after the war, returning to pageantry. In 1951 he led the production of the Three Towns Pageant at Hampton Court for the Festival of Britain, which was seen by 70,000 people – a considerable attendance for that period. In 1953 he even left Britain to write and direct the Pageant of Rhodesia in Bulawayo, which was visited by the Queen Mother and Princess Margaret. Four years later he produced the Pageant of Guildford, visited again by royalty, and this time of an even greater pedigree: the Queen herself, accompanied by the Duke of Edinburgh. As close as was possible in the circumstances, Bury St. Edmunds had replicated the coup of 1907, when they had bagged the father of historical pageantry, Louis Napoleon Parker.

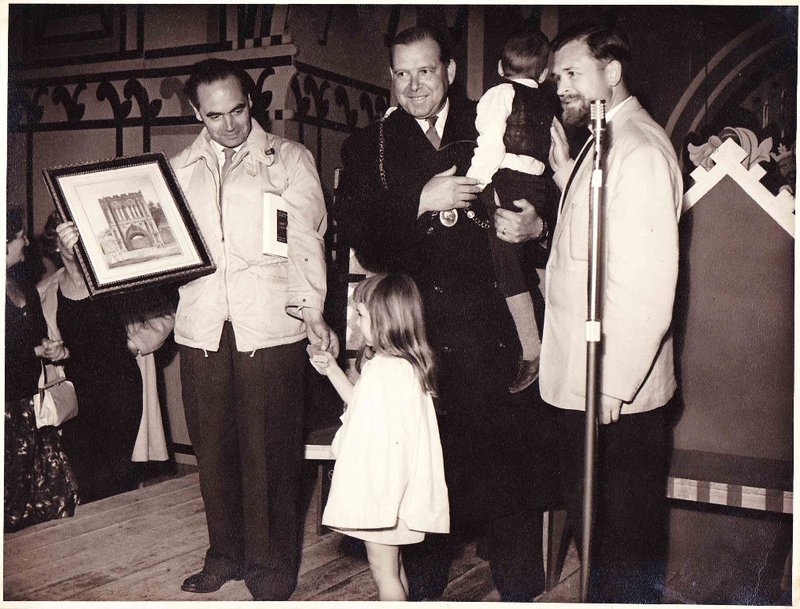

From left to right: The producer of the pageant,

Christopher Ede; Janet Downton; the Mayor of Bury St Edmunds, FG Banks; and the

author, Richard Tydeman. Janet remembers: "I was 4 years old and was

apparently the youngest person in the pageant apart from a baby. My mother Mrs

Maureen Lewis had some involvement with the costumes and I was dressed as a

peasant girl. [The photo is] of me presenting a picture to the mayor. I think

it was a drawing of the abbey gate." By permission of Janet Downton.

Back in 1907 the pageant had been a totally local endeavour. But, in 1959, the Borough Council was supported by the Magna Carta Trust, who were overseeing the triennial commemoration of the famous 1215 charter. A relatively new body, it consisted of various English and Commonwealth associations, and representatives of towns such as St Albans, Canterbury, and Egham (near Runnymede). Each of these towns was connected in some way to the original sealing of the charter – Bury St Edmunds's claim being the site of the famous meeting of the Barons in 1214, in the run up to the confrontation with King John the next year. The patron list for the Trust was impressive: the Archbishops of Canterbury and Westminster, the Moderators of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland and the Free Church Federal Council, the Chief Rabbi, the Lord Chancellor, the Speaker of the House of Commons, the High Commissioners for Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, India, Pakistan, Ceylon, Ghana, Malaya, Rhodesia and Nsyasaland, the American Ambassador, and the chairman of the executive committee of the National Trust. The Great and the Good from across the Commonwealth (and further!) had come together to celebrate the history of Bury St Edmunds. The main object of the Trust was simple: to perpetuate the principles of the great document, not just by celebrating its triennial, but by also encouraging a recognition of it as ‘the source of the constitutional liberties of all English-speaking peoples and a common bond of peace between them.’ Its work arguably reflected the postwar importance of redefining the politics of Commonwealth as the British Empire was gradually dismantled. On the Commemoration day for the event the distinguished guests included representatives from New Zealand, South Africa, India, Ghana, Malaya, Rhodesia and Nyassaland, and the USA.

Bury St Edmunds Pageant 1959 Amateur Photograph. By permission of Peter Wood.

In many ways the production of the pageant was updated for modern tastes. As well as floodlighting and amplified sound, the seventy-five speaking parts were mimed by the actors on stage, while a carefully selected panel of people seated at microphones, in a sound proof box overlooking the arena, spoke the dialogue. The music was also played from tape cassette, recorded by an orchestra and choir in the Cathedral two weeks before the first performance. The script was shorter than the 1907 pageant, and the dialogue was clear and easy to follow. There were also far fewer characters and incidents , and the inclusion of a Guide and a group of Tourists, who appeared in almost every episode, helped Ede and Tydeman explain to the audience what was going on. These contemporary figures also helped create a sense that the past was connected to the present – and through normal everyday people as well. In 1907, most of the leading roles were taken by the elite of the town, but, in 1959, the main characters were drawn from a much broader spectrum. King John, for example, was played by a junior director of a local shoe firm – probably due to him being a well-known and gifted amateur actor – while the Guide, the largest part in the pageant, was played by a geography teacher and amateur actor from the nearby Ixworth Secondary Modern School.

If anything, the pageant was simply a lot more fun. Ede’s style of pageantry was a recognition that entertainment had changed. As he put it a couple of years previously, ‘a public brought up on the cinema – and now on television – can scarcely bear to look at one incident for much more than ten minutes.’ A fictional and farcical election scene from the Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens was a chance to show bright colourful characters, bands, and a generally raucous atmosphere, while amusing japes were provided by an impatient old man even during important moments like the reading out of the Magna Carta. Gone was the excessive violence of the 1907 pageant, including the dramatic revolt led by Boadicea. The torture and death of Edmund, a main feature in 1907, now took place off-stage. Humour was given to local history, using both physical slapstick and more conventional, if now dated, jokes. In the second episode, for example, a lazy monk was pushed into a river – an unenviable role for the performer, who had to get wet everyday! In the same episode, one noble said to another ‘One does not tell everything to a woman’ to which his friend laughed and said ‘Indeed no’ – one of several jokes that would probably not suit contemporary tastes. King John again featured, in even more of a pantomime villain role than 1907, when he had been played with great panache by Moyse’s Hall curator Horace Barker.

Performers from Pickwick Papers episode. By kind permission of Peter Wood.

Two performers in between

scenes, with the grandstand in the background. By kind permission of Peter

Wood.

Performers between scenes -

props in the background. By kind permission of

Peter Wood.

Two young performers in the Bury St Edmunds Pageant

of 1959. By kind permission of Peter Wood.

But even if the pageant had been updated and made more amusing, there was still a serious point right at the heart of the performance. It was a chance to connect the small Suffolk town to a much larger, grander and ongoing national and international story – a goal that Edwardian pageants had always strived towards. The Mayor wanted visitors to enjoy the spectacle in the beautiful surroundings of the Abbey Gardens, but also to realise ‘how Freedom was gained slowly and painfully over the centuries’ so that it could be ‘cherished and protected by the generations that follow.’ WT Aiken, MP for the town, went as far as saying that it was in Bury St Edmunds ‘that the birth-pangs of English common law began’. The Magna Carta, and its connection to Bury St Edmunds, was thus given an almost mythical power by the Borough Council and the Magna Carta Trust.

The fated day in 1214, when the nobles came to Bury St Edmunds and swore on the shrine of St Edmund to challenge the tyrannous King John, was a vital part of this history, and formed a significant episode. In the following episode, one of the most visually arresting parts of the pageant, the barons thundered into the arena on horseback as if it was second nature – showing just how much the weeks of horse riding lessons had helped! As well as then showing the spread of democratic ideals throughout the country, there was also a children’s ballet scene that allegorically displayed the importance of the ‘great charter’. This was a ploy Ede had used at Guildford two years previously, and also elsewhere, probably having picked it up when working as an assistant producer for Donald Wolfit at the Pageant of Newarke in 1936. Two imposing dancers clad in back, representing Injustice and Oppression, at first enslaved other dancers representing ‘everyday people’. But they were then challenged by twenty-five colourful dancers, representing the Barons. When they failed, a figure representing Edmund led forward a younger dancer representing Freedom, dressed in white, carrying a large scroll, and with a Magna Carta symbol embroidered on her dress. Freedom beat back Injustice and Oppression, before giving smaller scrolls to the everyday people so they could defend themselves - a representation of the spread of Magna Carta ideals across the world. In the eighth episode, which was set in the USA in 1636, it was shown how the Body of Liberties drawn up by the General Court of Massachusetts was all based on Magna Carta – and thus linked little Bury St Edmunds to the governing of a superpower like the USA. Above all, the narrative of the pageant was about liberty. The World Wars, as presented briefly in the final episode, were shown as but short impediments to the continual growth of freedom. As the Guide put it, ‘Buildings may be destroyed and men must die but Freedom lives: her spirit is immortal.’

Ballerinas in between scenes. By kind permission of Peter Wood.

Ballerinas rehearsing. By kind permission of Linda Wicks.

The Bury Free Press was naturally gushing in its praise, declaring it ‘Brilliant’, ‘a magnificent triumph for players and producer’, and ‘a wonderful piece of civic enterprise.’ Ede, too, seemed happy with the result, and paid tribute to the collective spirit that had made it possible, telling the press that it had ‘proved better than I had ever hoped and this is entirely due to the team work of everybody concerned. It has been a long and hard job but the cast and staff have caught the spirit of the project, and this has made it the success it is.’ They concluded that the ‘splendid tribute’ made all in the town feel ‘proud’ about its ‘great heritage.’ There was too, of course, an element of trying to awaken the civic pride of the people of Bury, in particular to the towns ‘historic past’ and its ‘many beautiful buildings and historic associations’ that were taken ‘for granted’, as the Mayor put it. But when it came to deciding where the profits should go, the town did anything but pull together. The Mayor, councillors, clergymen, press, and local ratepayers all expressed different opinions, some with a surprising degree of vitriol. Ratepayers, who had essentially fronted the money for the pageant, thought it only natural that they should get to decide. But pageant performers also wished to make their voice heard, with some suggesting that the profit should be used to make tokens of appreciation, like medals, for all their hard work. Other more mundane suggestions included improving the public baths, providing playing fields, and even improving the sewer system.

After around four months of deliberation, the Publicity Committee finally decided to give the profit to the Cathedral Extension Fund - probably appropriate considering the pageant took place in the Abbey gardens and was strong on ecclesiastical history. But this also met with more heated debate in the council meeting. The decision was referred to the Development Committee for further consideration. It seems that disagreement arose for a variety of reasons. On the one hand, spending the money on a charitable purpose like the Cathedral would contravene a now-discovered original minute from early 1958 that had confirmed that any profit from the Pageant would go to the general rate fund. On the other, there was also opposition towards using the money for a cause that only benefited a certain community – such as the Catholic folk of the town. In the end the council came to what the Mayor described as a ‘happy solution’: no money for the Cathedral, but public shelters in the Abbey Gardens - something that would enrich the environ of the Cathedral while being available for everyone to use. A paved, open plan water garden was laid out, with a pair of shelters that looked distinctively of the period. This basic design remains today, though the garden has been enclosed, expanded with extra flowerbeds, and recently refurbished following a £40,000 donation.

Crowd scene. By kind

permission of Margaret Charlesworth.

Scene in the pageant. By kind permission of Margaret Charlesworth.

Despite the embarrassing money-wrangling, the Bury St. Edmund’s Magna Carta Pageant was an undoubted success. Over 50,000 visited the pageant grounds to see one of the 12 performances, including many from surrounding American army bases. It made a decent profit of £2,158, 17s 11d – about £33,000 in today’s money. It was a triumphant return to the ideals and achievements of the original event in 1907, achieved through newer methods of production. Throughout the two weeks there was a sense that it the spirit of 1907 remained. The Mayor said that he had been constantly reminded by older people of the original pageant, ‘the greatest venture the town ever embarked upon’. The Bury Free Press was only too happy to play up this connection, printing photos of episodes from 1907. Links were expressed remained in other ways as well. Some of the old chain mail was used, and many from the original took part again in 1959. If the possible irrelevance of traditional forms of historical pageantry in the 1960s and 1970s seems obvious to our eyes now, it was not quite as clear at the time. Thus, the success of the 1959 pageant almost certainly encouraged the consequent decision to hold the pageant-play, ‘Edmund of Anglia’ in 1970 – a return to pageantry, but one that was fraught and challenged.