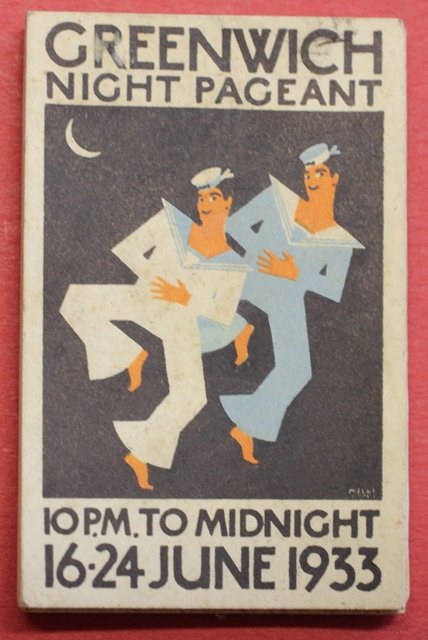

The Greenwich Night Pageant 1933

*Guest post by Dr Emma Hanna, Senior Lecturer at the University of Greenwich*

Using the grounds of the Royal Naval College as its stage, the Greenwich Night Pageant of 16th-24th June 1933 sought to showcase important episodes in English history. Various tableaux, including the christening of Elizabeth I, Drake’s arrival on The Golden Hinde, and the funeral of Nelson were re-enacted by a huge cast. Accompanied by sea shanties and Sir Henry Wood’s Fantasia on British Sea Songs, ten two-hour performances were seen by over 120,000 people, including prominent politicians and royalty. The pageant was produced by Arthur Bryant, one of the most successful Producers of interwar Britain. He was appointed in the spring of 1932 under the auspices of the Greenwich Night Pageant Company Limited, and was offered payment of £400 - including expenses – around £15,000 in today’s money. The Company was run by Admiral Barry Domvile, Principal of the Royal Naval College 1932-34, and his wife Alexandrina, the driving force behind the event.

Pageant sticker. Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives - Bryant J6 Folder 3

Early plans laid out by Domvile in 1932 detailed that the Pageant ‘will be largely Naval in character and is intended to show the interest displayed by the various Sovereigns in Naval affairs and the gradual development of the Navy under their auspices.’ Of the Royal Naval College Domvile said that ‘the setting provided for such a show is very nearly ideal, and the History of Greenwich is the history of England, because a Palace has stood on this site since the 15th century. Both King Henry VIII and Elizabeth I were born at Greenwich, and to Greenwich came Sir Francis Drake in his famous GOLDEN HIND [sic.] to make his bow to his queen. From the Painted Chamber at Greenwich Nelson’s coffin was borne down to the river to be carried to its final resting place in St Paul’s. [...] Apart from this the National Maritime Museum with its valuable and intensely interesting treasures will be inaugurated shortly [...] in the Queen’s House at Greenwich. ’

Sir Barry Edward Domvile by Bassano Ltd, vintage print, 21 December 1932, Photographs Collection, National Portrait Gallery: x84085

The Greenwich Night Pageant was understood as a naval alternative to the RAF’s annual display at Hendon and the Army’s Tattoo at Aldershot. Greenwich certainly had the support of the Royal Navy which was underlined when Earl Beatty paid a well-publicised visit to witness a dress rehearsal.[4] Beatty underlined that Greenwich was ‘almost the birthplace of the Navy’ surrounded as it was by Royal Dockyards, and that he hoped the pageant would teach people about the Navy’s history. The event was heavily publicised, appearing in 480 publications of local, national and international coverage running to over 5000 column inches. The press were treated very well and were transported to report on two dress rehearsals by riverboat. The revival of the Whitebait Ministerial Dinner on opening night – a 19th century tradition where the Cabinet travelled to Greenwich by boat –ensured that the event made front page news. The event was also highly accessible. The Pageant ticket office was close to Greenwich station, and the prices of seats range from 1s 6d [£2.77] to 12s 6d [£23.11]. A fish dinner was advertised in the Painted Hall at 5s 6d [£10.17]. All forms of public transport planned to offer extra services to supply the demands of the Pageant, and Empire Shopping Week was also held at this time.

Book of the Greenwich Pageant 1933. Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives - Bryant J6 Folder 1

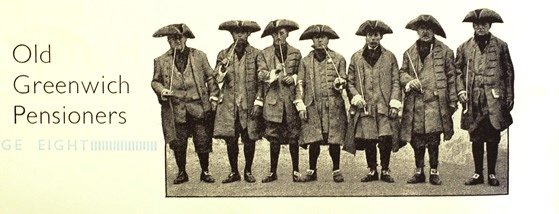

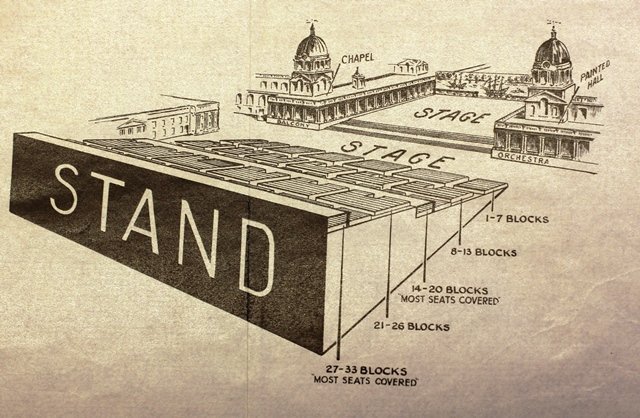

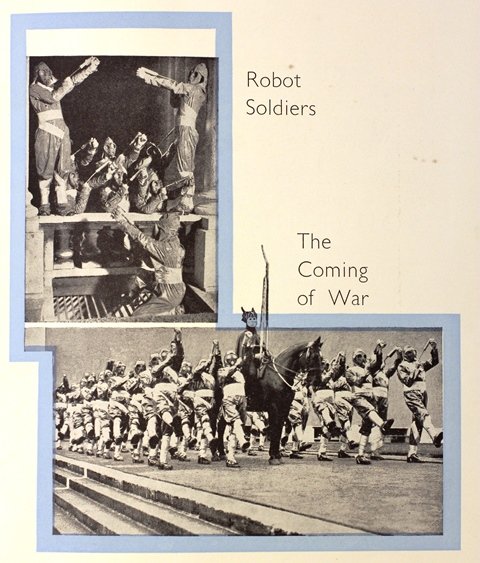

The cast of the pageant was vast. Approximately 2500 local people acted, and many were drawn from various organisations including The Old Contemptibles Association and local youth and athletic groups. The sense of place was key. The buildings of the Royal Naval College were used as a set, the colonnades acting as wings and the steps between as additional stage space. The most striking, unique and effective part of the pageant was the use of the Shadowgraph. A screen 33 feet wide and 120 feet high was erected between the colonnades of the King William and Queen Mary buildings which allowed for the projection of lantern images in large scale. This system was invented by Dr B. P. Haigh, Professor of Applied Mechanics at the College and was of particular interest to the press. Models of ships were run along a small railway track in front of the lantern, at an angle which represented the approach and withdrawal of the vessels. Stencil slides were also used to project dates, for example, and the sea was represented by wave effects. But it was these technical elements of the pageant which made it both unusual and extremely challenging for Bryant and his team. He wrote that ‘[it] is quite unlike the ordinary Pageant in its stage technique, and its production is much more the kind of work to which a producer of films is accustomed than a Pageant Producer.’ Punch magazine described the Shadowgraph as ‘entirely novel in the way of silhouettes, the undistorted movement of which across the screen is amazingly realistic.’

Pictures of the Greenwich Night Pageant (1933). Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives - Bryant J6 Folder 1

Pageant Stand. Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives - Bryant J6 Folder 2

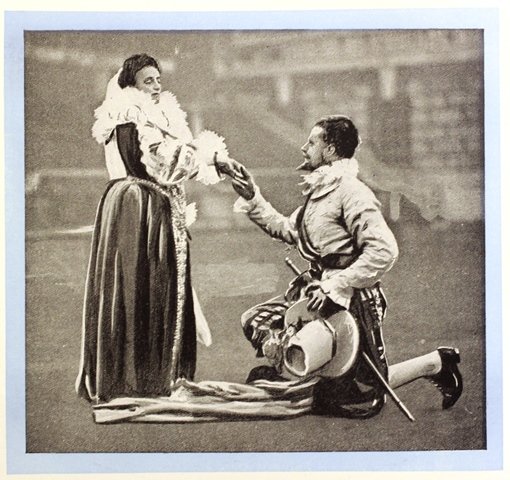

The Greenwich Night Pageant was typical in the prominence it gave to the Tudor period. The was indeed dominated by Elizabeth and the hero Drake, and as recently as 1930 the Aldershot Tattoo had incorporated a pageant of Elizabeth I addressing her troops at Tilbury. However, the Pageant’s version of British history ignited debate in the national press. Isaac Foot, a Labour MP, addressed the First Lord of the Admiralty in the House of Commons asking why the pageant failed to reference ‘the Protectorate and the Commonwealth and the supreme services rendered to the British Navy by the Great Protector, by Vane, and by Robert Blake.’ Bryant responded that it had purely been a matter of space, time and continuity. He said ‘the only dramatic episode in the great Admiral’s life which we could have presented adequately was his funeral [...] We chose Nelson’s, and honoured Blake in the only way left to us by making him the central figure of our posters’. Foot replied that while public duties had denied him the privilege of watching the Pageant, he appreciated ‘the beauty and the public spirit of the enterprise [but he] regarded the presentation in one respect as a perversion of our national history.’

Elizabeth and Raleigh - Pictures of the Greenwich Night Pageant (1933). Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives - Bryant J6 Folder 1.

Pictures of the Greenwich Night Pageant (1933). Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives - Bryant J6 Folder 1. For more on this episode, see here.

Domvile was knighted in 1934 quite possibly as a result of the successful staging of the pageant, which made over £3000 [£110,000] for local and naval charities. However, once he had retired from the Navy Domvile’s political views and subsequent activities led to the event being quietly forgotten. He made the first of many visits to Germany in 1935, where he mixed with senior Nazi officials, and he became very critical of British policy and the ways in which British newspapers represented Germany. He and his wife founded a pro-German organisation called The Link in 1937 which had over 4300 branches across the UK. Domvile, his wife and his two sons were all under MI5 surveillance from at least the mid-1930s, although no reference is made in their file to the Greenwich Night Pageant. In July 1940 Domvile and his wife were arrested under 18B regulations; Alex went to Holloway and her husband was imprisoned with Oswald Moseley in what he referred to as ‘His Majesty’s stone frigate on Brixton Hill’ until November 1943. It is unsurprising that this later history has led some historians to refer to the Greenwich Night Pageant as ‘as close as England came to fascist theatre’.[1]

[1] Kevin Littlewood and Beverley

Butler, Of Ships and Stars (London:

Athlone, 1998), p.61.

Other Sources used:

Liddel Hart Centre for Military Archives: Bryant C22

Kentish Mercury

Lloyd’s List and Shipping Gazette

The Times

Richard Griffiths, Patriotism Perverted: Captain Ramsay, The Right Club and British Anti-Semitism, 1939-40, (London: Constable, 1998)

The National Archives: KV 2/834

Admiral Sir Barry Domvile, From Admiral to Cabin Boy, (London: Boswell, 1947)

Kevin Littlewood and Beverley Butler, Of Ships and Stars (London: Athlone, 1998)