The Pageant of Bury St Edmunds 1907

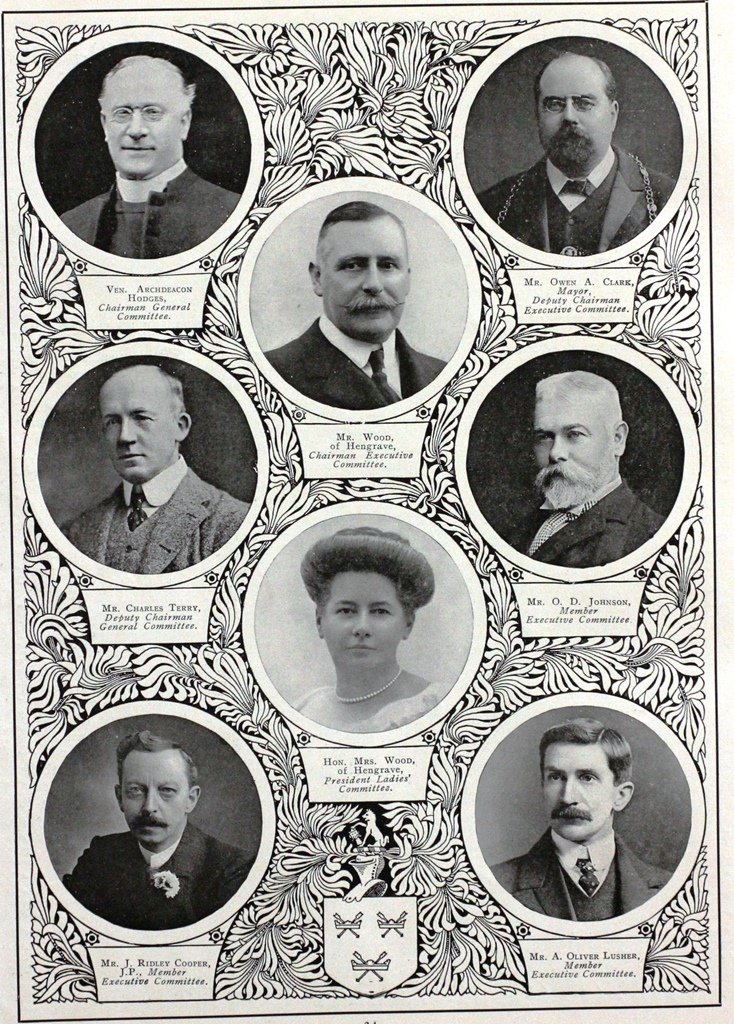

The Bury St. Edmund’s Pageant of 1907 was a major and spectacular event, reported locally, nationally, and even internationally. It came in the initial flurry of historical pageants that had spread after Louis Napoleon Parker’s first extravaganza in Sherborne, Dorset, two years previous. Almost straight away Bury St Edmunds sat up and took note, and began planning for their own, the initial suggestion having come from the Venerable Archdeacon of Sudbury and Vicar of St James's, Bury St Edmunds, George Hodges, who also went on to play Abbot Samson. He was supported from the beginning by the civic and municipal worthies of the town, many of whom took leading positions on the various committees. The town managed to entice Parker to the small Suffolk town to produce their effort – the only one that the original pageant-master agreed to that year. High expectations unsurprisingly grew, and the pageant didn’t disappoint. From any perspective it was a leviathan task, with 1800 performers (not far off an eighth of the town’s population!), and a huge choir and live orchestra. Staged eleven times in July, the performance lasted a lengthy three hours, with lots of dialogue throughout. A financial and artistic success, lauded widely across Britain, Bury St Edmunds’s first historical pageant was still a fond memory in the town when ‘pageant-fever’ again broke out in 1959 for the famous Magna Carta Pageant.

A typical crowd-scene in the seventh episode - Postcard - by kind permission of the St Edmundsbury Heritage Service

It was, in every way, a classic Parkerian pageant. The costumes and props were made in the town, or paid for by the 1800 performers - who were almost all local amateurs. The Times, in many positive reports about the preparations, calculated that the voluntary work and actual monetary contributions would have amounted to a total cost of £100,000 – a whopping £5,735,000.00 in today’s money! It’s not surprising that, with all this effort, a visiting journalist found that the spirit of pageantry had taken root everywhere across the town. Interviewing performers and volunteers, he painted an intriguing picture of hustle and bustle, but also a bit of confusion. One man, playing a Rabbi, summarised the breadth of opinion: ‘Some people here makes out it’ll benefit nobody but the Hotels and Mr. Parker – that’s the master of the ceremonies – but I think if history is going to draw at all we’ve got as good a chance as anybody.’ A housepainter, who took the part of St. Swithin, was enthusiastic about his role, but admitted he hadn’t any clue yet what his lines were, or with which woman he had to hold hands! The grand Angel Hotel, opposite the ancient Abbey Gate and famed for its association with Charles Dickens, was temporarily transformed into ‘Pageant House’ – the headquarters of the event. Here the journalist found many of the handsome large rooms re-used as offices, changing rooms, and workshops, where young men from every section of society came in each day and every evening to take their turns at the benches and lathes. Equally impressive was the commitment of the 1000+ ladies who were determinedly making dresses.

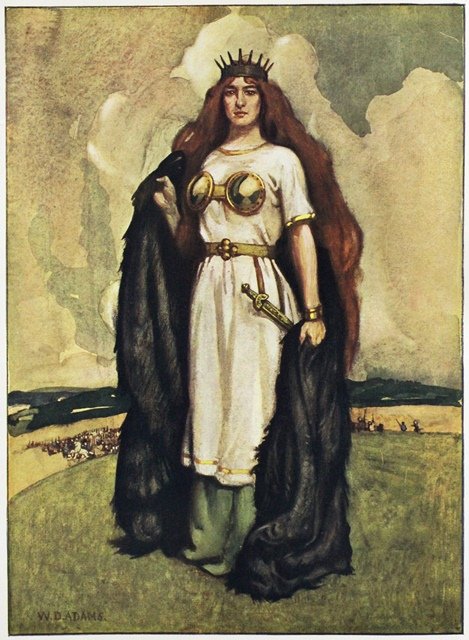

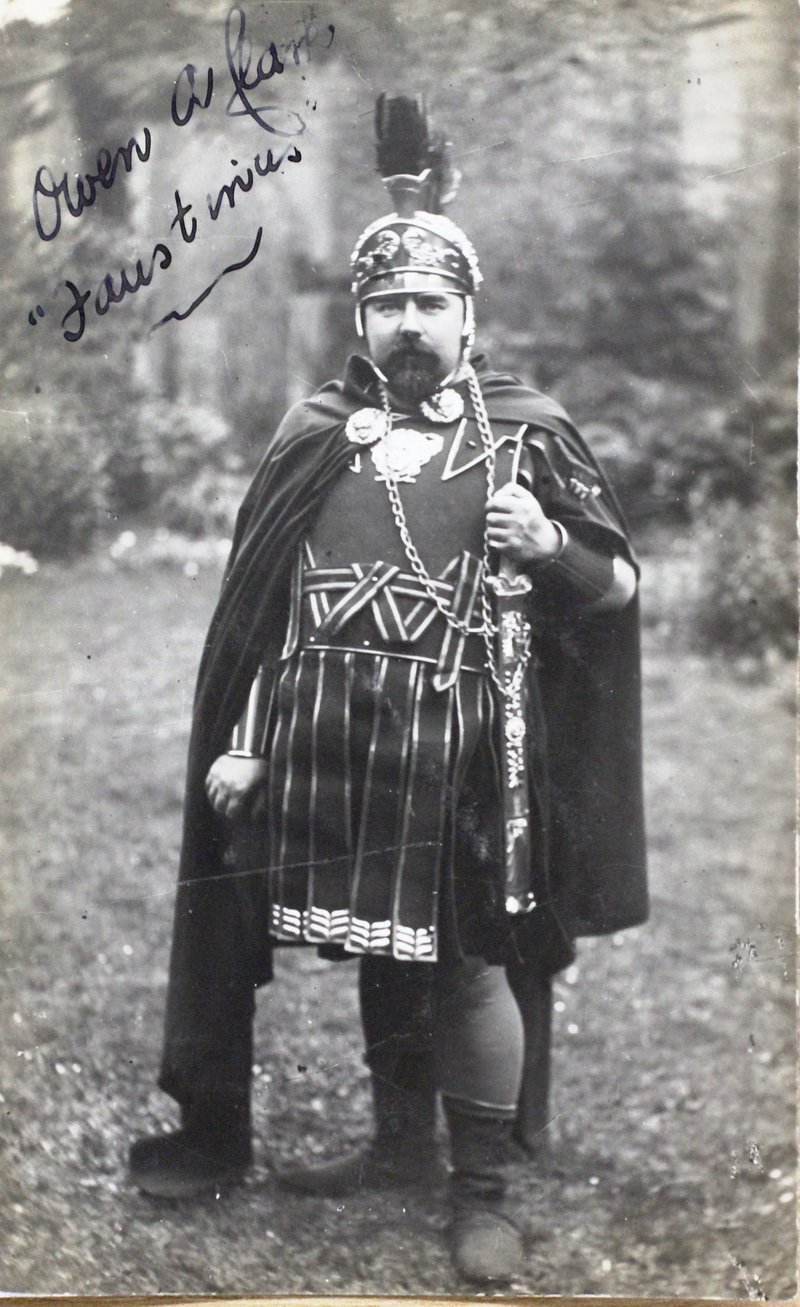

The themes of the actual performance would have been instantly recognisable to spectators already familiar with Edwardian pageants. The story began with the Roman occupation and the exploits of Boudicca. Portrayed as a particularly fearsome warrior, the action in reality had only the most tangential links to the actual established history of Bury St. Edmund’s. But when she roared into the pageant arena in a proper horse-drawn carriage, it must have made the audience sit up and take notice. Probably the most interesting aspect of the episode was the decision to cast the Mayor as Faustinus – a drunken and arrogant embodiment of the tyranny of the Roman reign. The fifth episode, which featured a condensed version of Shakespeare’s Henry VI was also a common pageant ploy – and, again, not particularly relevant to Bury. But, apart from these two episodes, the pageant was a whirlwind exercise in local history. The second scene set King Edmund as the key character of the narrative. After displaying his fairness and holiness he was horrifically martyred for refusing to renounce his religion – an emotive example of both sacrifice and piety. Despite his death in this episode Edmund literally haunted many of the other episodes, as the essence of his spirit guarded the town and its Abbey from the misdeeds of outsiders – such as in Episode III (A.D. 903), when his spear miraculously slayed the slave-making Dane, Sweyn; in Episode IV (AD 1198) when King Richard was dissuaded from trying to overrule the Abbot after being threatened with the spirit of Edmund; and later, in the same episode (A.D. 1065), when a usurping Bishop, Herfastus, was struck suddenly with blindness.

Boadicea - Water-colour drawing by W. Dacre Adams in The Connoisseur, 3rd Special Edition (1907) – by permission of St. Edmundsbury Heritage Service.

Boadicea in a postcard of the pageant - by permission of the St Edmundsbury Heritage Service

Signed postcard of Mayor Owen A Clark as Faustinus - postcard - by permission of the St Edmundsbury Heritage Service

But the shrine of Edmund was not just a ghostly teacher ne'er-do-wells. A succession of more pious King’s and Queen’s also lined up to visit, effectively linking the story of Bury St Edmunds directly to the history of the country by designating the town as a place that was important and respected. In Episode III (A.D. 1035), for example, Canute lay his crown on the shrine in atonement for the sins of his father, the aforementioned Sweyn; later, in the same episode (A.D. 1044), Edward the Confessor made a pilgrimage to the shrine, as did King Henry I (A.D.1095). This theme continued in the fourth episode, when King Henry II and Queen Eleanor visited to pay homage (A.D. 1189). The most important visit of all was that of the tyrannous King John I in A.D 1203. John was played by the curator of Moyse’s Hall, Horace Barker, in a particularly spectacular and luxurious costume. A popular pantomime villain of historical pageants, John was shown essentially stealing the jewels of the shrine through sneaky tricks. This plot device was vital for the next episode, where twenty-five Barons met in A.D. 1214 to set in motion the ‘brave rebellion’, swearing – of course – on the shrine of St. Edmund. Parker also made sure to feature the ‘spectacular’ scenes to which pageantry lent itself so well, such as big battles, the fun of the fair and Morris dancing, and space for the pageant favourite, Queen Elizabeth, to appear in the final episode.

Horace Barker as King John - postcard - by permission of the St Edmundsbury Heritage Service.

Queen Elizabeth and her Retinue, Episode 7 - Postcard - by kind permission of the St Edmundsbury Heritage Service

Robert Fitzwalter reads the charter to the Barons- Water-colour drawing by W. Dacre Adams in The Connoisseur, 3rd Special Edition (1907), a special souvenir edition for the pageant – by permission of St. Edmundsbury Heritage Service.

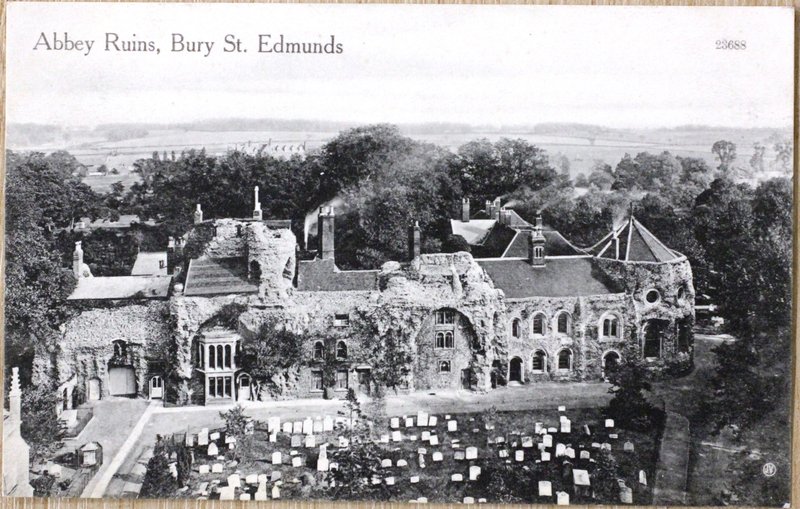

Taking place in the Abbey gardens, with the glorious and imposing ruins of the Abbey, Parker had a point when he told the Observer that ‘Bury St. Edmunds is steeped in English history to quite an extraordinary degree, and, therefore, affords special opportunities for a successful pageant’. The Standard also declared that ‘A little town with a great history, and, for motto Sacrarium Regis Cunabula Legis [Shrine of a King, Cradle of the Law], is just the place for the organisation of a historical pageant.’ These themes were pulled together in the final chorus, which detailed a patriotic vision of England and of Saint Edmund, and Bury St Edmunds’s place within the story as the ‘shrine where liberty had birth.’ As Saint Edmund appeared on the pedestal at the back, the National Anthem was sung, before the entire cast marched past. When Saint Edmund departed, the pageant had ended. The Antiquary, a publication generally enthusiastic about historical pageantry, was straight-to-the-point in linking the local spirit for romantic re-enactment to the renewal of a more general patriotism. Revelling in the patriotism of Bury St Edmunds’s, the magazine mistily described how many, with ‘the sweetest air in England’, would also suck in ‘a deeper and fuller patriotic enthusiasm’. Parker himself often made the same point. He now told the Observer, in a lengthy and jovial interview, that arousing ‘local interest in local history’ would increase both the dignity and self-respect of Bury St Edmunds, while also encouraging the preservation of local antiquities and local architecture.

Postcard - by permission of the St Edmundsbury Heritage Service

Dr Ernest Stork as King Edmund - postcard - by permission of the St Edmundsbury Heritage Service

For Parker and other pageant-masters, it was also important that pageants could help create stability. All sorts of people, Parker believed, would be given opportunities to show-off their hidden talents, since pageants embraced everybody: peer and peasant, millionaires and poor, men, women, and children. His invention was a conscious attempt to create a bulwark against both the rising class conflict of the Edwardian years and what he argued were the damaging consequences of architectural and social modernity. The Bury Free Press was happy to back him up in this respect, telling its readership that the pageant was a result of both individual and collective effort where the nobility fraternised with the humbler classes – all desiring to help portray the town’s grand history.

But, if the pageant aimed to temporarily dissolve distinctions of class, it was at the same time helping to shore them up. Most of the prominent performing roles went to the civic elite, such as Mayor Owen A Clark playing Faustinus, or the Archdeacon of Sudbury, George Hodges, playing Abbot Samson. The town council also eagerly took up the chance to lavishly celebrate its own power and position, with exclusive luncheons, traditional civic processions, and – of course - the best seats in the grandstand to watch the pageant. Most in the town might have taken part, but not all were equal in the strictest sense of the word. Not surprisingly, the pageant also swerved away from showing memorable examples of revolt and challenges to local authority. Most conspicuous by its absence were the fourteenth century riots, when disgruntled townsmen had burned the Abbey to the ground and pillaged the library. Like the Times hinted, it was wise to not feature aspects of history that interfered with the goal of giving reverence for the past, and a sense of continuity from it. At the same time, however, the pageant was still a chance for all in the town to be involved in some way - people decided their own level of commitment, and it seems undeniable, especially from the photos, that most people were enjoying themselves!

Predictably, the trusty British weather disrupted some of the performances. One afternoon the rain came down so hard that the final tableau was cancelled, songs and dances were left out, and poor Boadicea had to walk into the action rather than thunder in on her usual horse-pulled chariot. These setbacks robbed the show of some of its glory - though humour must have been found in Cardinal Beaufort wearing a modern mackintosh to keep out the rain! According to the Daily Express, no amount of rain could dampen the enthusiasm of the pageanteers. Following the worst, Parker played-up the ‘wonderful pluck’ shown in the drenching rain’ in a note to his performers: ‘TO THE HEROES AND HEROINES BIG AND LITTLE OF YESTERDAY, The Water Pageant was the greatest triumph we’ve had yet! You swam through your episodes like ducks. We have a great audience to-day. Let’s show ‘em what it’s really like! Silence! Invisibility! Briskness! High Spirits!’ The show must go on!

Morris Dancers - Postcard - by kind permission of the St Edmundsbury Heritage Service

Public opinion was almost entirely positive. The local Bury Free Press, of course, went over-the-top in its praise, describing the pageant as ‘imposing, glorious, and soul-stirring’ and ‘one of the grandest spectacles of modern times’. The Athenaeum, in a detailed report, praised the setting, the flamboyant costumes, the realistic armour, the excellent acting, the dances, and the props. The journal had only mild criticisms – and fussy ones at that – such as the ‘mistake’ of giving ‘the gaudy Cardinal Beaufort, in the fifteenth-century episode, a broad-brimmed hat of a much later date’ or the same performers lack of ‘concealment’ of his moustache. They also noted the incorrect number of monks in Episode VII (38 when it should have been 42, and what they saw as ‘the wrong impression… as to the supposed dawn of learning under Edward VI.’ Such astute observations, pernickety as they were, reflected the seriousness that many reporters gave to the accuracy of historical pageantry.

Other newspapers were shorter in their opinions, but a tone of approval still dominated. The Observer called it ‘a triumph in pageantry’; the Times described the ‘spectacular effects’ as ‘perhaps the most splendid’ Parker had yet created; the Dover Express dubbed the whole event ‘a glorious example’ for their own upcoming pageant, also to be directed by Parker; and a writer for the Ladies Column in the Derby Daily Telegraph claimed ‘Never have I in my life seen any spectacle which has pleased and charmed me, and has excited my imagination, as has done the Abbey Pageant at Bury St. Edmunds.’ That so many local newspapers from across the country reported the pageant of Bury St Edmunds in such depth shows the newsworthiness such a small event could have during this period of ‘pageant fever’. Even the famous American author Mark Twain, an enthusiast of pageantry after seeing the Oxford Pageant twice, expressed his excitement about Bury St Edmunds’s effort – though, in the end, he couldn’t actually attend.

When it came to deciding what would be done with the profits, £1044.0.6 or about £60,000 in today’s money, the debate was had out in the open. One of the first suggestions was for the erection of a statue of Cardinal Langton handing a copy of Magna Carta to a figure of liberty which would, a local historian told the Bury Post, ‘appeal to the imagination of the liberty loving Anglo-Saxon race for all time’. To help decide the Pageant Committee put out an advertisement in the Bury Free Press asking for suggestions. At least thirteen people responded directly, with suggestions, such as: a permanent winter fund for the poor, to be called the Pageant Bread and Coal fund’; a maintenance fund for the abbey ruins; a children’s ward at the local hospital; and even a new golf course (as the Mayor himself favoured!). But the most frequent suggestions were for something that would help the lot of the poor and working classes. As an ‘absent well wisher of St. Edmundsbury’ told the Bury Post,

We have had our Pageant… What have we learned from our past history, and what fruit are we going to show as the result of that lesson? Bury has paraded in fine clothes, and reproduced many noble acts in pageant, but what has she learned to do in deed, or was the lesson all in vain? What is she going to do for her unemployed this winter, and the families who are in cold and want? It is cold comfort, and will not fill hungry stomachs, to say it is their own fault. Cannot something be done? Cannot the Pageant surplus be used for some relief works? Cannot that spirit of brotherhood and co-operation evidenced and stimulated by the Pageant be used to make, not to act, history, to do noble deeds in work-a-day clothing, and humdrum circumstances. Surely that is better and nobler than parading in the fine clothes of others, and telling their deeds; it were better to copy them.

Eventually a sub-committee was set up to consider the matter. It decided that it’s own choice would be for the Town Council to acquire the Abbey Gardens for public recreation, and the profit for the restoration of the Abbey gateway. As the town council could not agree terms for the Gardens, they instead recommended a sanatorium to tackle Tubercular disease, especially for the ‘poorer classes’. Tuberculosis was certainly a pressing matter, having accounted for almost 10% of deaths in the town in the previous year. In 1909, the year after the decision was finally made, the Bury St. Edmund’s and West Suffolk Sanatorium was opened.

Lauded by critics and financially successful, the pageant had provided a ‘call to arms’ for the residents of Bury St Edmunds. Many thousands helped to create the spectacle, and tens of thousands more saw a performance. The importance of the event in the social calendar of Bury St Edmunds for that year is obvious, but so was its lasting legacy: when the town decided to hold another pageant in 1959, many of the episodes were recycled and modernised as the town again celebrated its long and esteemed history.