St Albans 1948: an austerity pageant

On 21 June 1948, The Times reported that the small Hertfordshire city of St Albans was getting ready for a pageant:

This week-end the streets and shops and houses of St Albans are gay with bunting and the city’s blue flag with its golden cross can be seen at every mast as the people make ready to celebrate the thousandth birthday of five foundations – three churches, a school, and a market. Down on the smooth meadows by the lake the covered stands are ready, if not literally under the shadow of the abbey certainly under its dominating grandeur and influence, for the pageant that will be played all this week and watched by the Queen on Tuesday.

The Millenary Pageant of 1948 was the second time a historical pageant had been staged in St Albans. The first was in 1907, during the wave of ‘pageant fever’ that swept Britain before the First World War. This had involved 3,000 performers and a choir of 200, and there was a grandstand with a capacity of 4,000. A reasonable profit had been made, shared between the local museum and hospitals. The 1907 pageant had depicted eight scenes of local history, ending – as was typical – with a visit to the town by Elizabeth I.

Episode 3: ‘Ulsinus Has a Plan’ (948 AD).

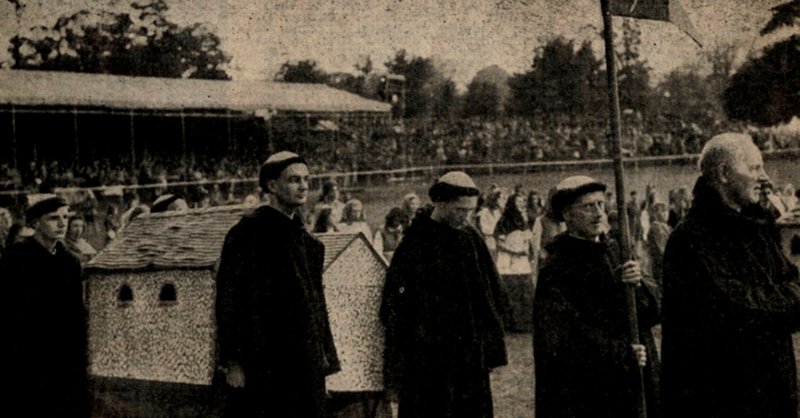

Forty-one years later, St Albans staged its second historical pageant in Verulamium Park, amid the ruins of the Roman town that had stood on the site. The early post-war years, particularly the 1950s, saw another outbreak of ‘pageant fever’, but St Albans was one of the earliest of the post-war pageants. The idea seems to have come from the General Purposes Committee of the city council, which first suggested a pageant in November 1946. The timing was particularly appropriate: as The Times noted, 1948 was the 1,000th anniversary of the foundation of the town, school and churches of St Albans. The pageant depicted scenes from the Roman era, through the medieval and early modern periods, and ended with an episode set in the nineteenth century. Two scenes stand out in particular. ‘Ulsinus Has a Plan’ was set in 948 AD, when, according to tradition, abbot Ulsinus or Wulsin laid out what would become the town of St Albans, and established the school and the three churches of St Stephen, St Michael and St Peter. In this scene performers carried models of the three churches into the pageant arena. The last episode, ‘St Albans Is a City’, depicted the joyful celebrations that accompanied the royal charter of 1877 elevating St Albans to city status, as well as the creation of the diocese of St Albans in the same year. Here members of the city council, including the mayor W. R. Hiskett, played their own predecessors from 1877. Other scenes included the martyrdom of St Alban, the establishment of the abbey by King Offa in 793 AD, and bribery and corruption at the general election of 1722. There was also a visit by Elizabeth I to Sir Nicholas Bacon, father of Francis, at nearby Gorhambury House in 1572.

Episode 9: ‘St Albans Is a City’ (1877). The city councillors played their own predecessors in this scence.

The pageant-master and script-writer of 1948 was Cyril Swinson. Born in St Albans in 1911, Swinson was a publisher and author, who wrote under the pseudonym Hugh Fisher. He was a founder member of a local theatre group, the Company of Ten, which is still in existence. Swinson’s brother Arthur, also a prolific author and radio and TV scriptwriter, was ‘Marshal of the Arena’. Cyril Swinson went on to produce many more pageants in the 1950s and early 1960s, before his premature death in 1963. He was not, however, the council’s first choice, either for script-writer or pageant-master. Ambitiously, they first approached the author Dorothy L. Sayers to write the script. She declined, and the council then asked Lawrence du Garde Peach, who had been a notable theatrical figure during the interwar period, and who later wrote the Ladybird Books Adventures from History series. Peach, however, demanded a fee of 250 guineas, which was beyond the means of the council. The first choice for pageant-master was also too expensive, and so Swinson took both roles, and almost by accident launched himself on a career as one of the most prolific pageant-masters of the post-war era.

Preparations for the pageant of 1948 were heavily affected by post-war austerity. By September 1947, arrangements for the pageant were in place, but the council reported that ‘the economic state of the country as a whole led to grave doubts as to whether the Pageant would be allowed to take place at all’. The council consulted Stafford Cripps, the Minister of Economic Affairs, and the Home Secretary James Chuter Ede. Although it is not clear what these senior government ministers told the council, it was decided to scale down the ambitious aims for a pageant with 2,000 performers, and instead to stage a ‘pageant-play’ with 500 or 600. A pageant-play would have less spectacle and more dialogue: this meant that it would be cheaper to stage, but that it would require more rehearsal. Smaller pageants had taken place since the war, notably at Chilham Castle in Kent, where 600 performers were watched by a total of more than 10,000 people in 1946. St Albans drew inspiration from the pageant at Chilham.

Flyer advertising the St Albans Millenary Pageant.

In the end, a cast of around 1,000 appeared in the St Albans pageant, which featured some of the spectacle of the Edwardian and interwar pageants, but at a more modest cost. The costumes were under the direction of ‘Mistress of the Robes’ Mrs J. Miller, ‘many ingenious ways being found to overcome the shortage of suitable materials’. The expected cost of the pageant was reduced following confirmation that the pageants would not be subject to the entertainments tax, on the grounds that it was ‘of a wholly educational nature’. As the council reminded the government, some of the performers were schoolchildren. The entertainments tax was levied from 1916 to 1960, in the face of much opposition, and it was a relief for the organisers of the St Albans pageant to be granted exemption. A souvenir programme, containing the full script of the pageant, was printed on the thin paper characteristic of the period, and priced at 2s.6d. It contained advertisements for many local businesses, some of which invited visitors to come and see their premises. In the early post-war years St Albans was a designated ‘expansion town’, and was aiming to attract new industries and residents.

Civic pride was at the centre of the pageant. According to the American pageant-master William Chauncy Langdon, ‘the place is the hero’ of a pageant, and this was certainly true at St Albans. There was a specially written pageant hymn, singing the city’s praises; the city flag was flown from the town hall for the duration of pageant week; and there was an associated exhibition of city charters and corporation plate in the museum. Swinson’s avowed aim was ‘to stimulate pride in the city’. The highlight of the pageant – and, for various reasons, the occasion of the most memorable performance – was the visit of Queen Elizabeth, the future Queen Mother, on 22 June. This provided an opportunity for ceremony: the ‘civic heads’ were presented to the Queen before the pageant, and others got to meet her afterwards. According to one local historian, the arrival of the Queen was a beautiful moment: ‘a beautiful rainbow seemed to encircle the Abbey [i.e. cathedral] tower … the most spectacular effect that any producer could have dreamed of’. Another member of the audience, however, had a different recollection of the night of Her Majesty’s visit. During the finale, a lone horseman led the entire cast on a march past the royal box – and at this very moment the horse let out a long and loud fart, which lasted the whole hundred yards of its walk.

Postcard of St Albans town hall, displaying a banner advertising the pageant.

Wide local participation was an important feature of the pageant, and Cyril Swinson emphasised the benefits to the whole community that the event could bring. Even those with little interest in history, he thought, benefited from taking part in the organisation of the pageant. One participant enthusiastically remembered:

Nobody who has not been in a pageant can truly savour the atmosphere which pervades the community. After some weeks of rehearsal in church halls or rain-sodden fields the great day finally arrives. Thousands of people throng the streets leading to the arena and are bustled aside by scurrying monks, mediaeval ladies on bicycles munching sandwiches as they pedal, choleric cavaliers trying to inch their cars through the mob as they reflect on the dinner they will not have, Roman soldiers steering an erratic course through it all with demure Regency ladies simpering on the the pillions, all, in our case, converging on the site of the Roman city of Verulamium.

This is not to say that everything went smoothly. Despite the

council’s support, the Highways, Buildings and Works Committee was

unwilling to allow banners to be hung across the street to advertise the

pageants. There were also arguments about who should play in each

scene, and opposition to the whole thing from a ‘faction’ inside

Swinson’s own Company of Ten. Some took the opportunity to complain

about post-war austerity and high levels of local taxation. In a letter

to the local newspaper, one resident imagined a pageant scene set in

1948 itself:

We will show you how in ’48

St Albans lived, and what they ate

Honoured Bacon in their fashion

Subsisted on a two-ounce ration.

Records tell how Mayor Hiskett

Had for joint a bit of brisket.

Supplemented by a tin of bully;

Waists were not expanded fully.

But old Albanians as in war

Instead of clamouring for more,

Beneath the rationing blows then dealt

Just smiled, and tightened up their belt.

The City Fathers at that date

Extracted a nineteen-shilling rate.

Queues which formed for stuff to eat

Stood mortionless in Peter-street.

So praise the men of ’48

Who stood the buffetings of fate.

From the local newspaper, monks carrying a model of St Stephen’s Church, with the grandstand in the background.

Despite humorous carping like this, the pageant was widely held to be a success. Paper rationing meant that it was not well reported locally, but, according to one recollection, it ‘captured the imagination of the Press and public the world over, especially as it was one of the first touches of glamour and frivolity after the grim war years’. With substantial takings from ticket sales, as well as a souvenir programme and car park, the pageant made a profit of more than £3,000. This was spent on a home for the elderly, and encouraged St Albans to stage its third pageant in 1953, also with Swinson at the helm. The 1953 pageant, entitled ‘A Masque of the Queens’ in honour of the coronation of Elizabeth II, involved 1,600 performers and had a grandstand capacity of 4,000. However, unlike the 1948 event it made a substantial loss, and St Albans never staged a large-scale outdoor pageant again. There was an indoor pageant-play in 1968 – of which more another time.

NOTES

All images courtesy of St Albans Museums, who are a project partner on the ‘Redress of the Past’ project. For more details of the 1948 pageant, see the database entry here. See also Mark Freeman, ‘“Splendid Display; Pompous Spectacle”: Historical Pageants in Twentieth-Century Britain’, Social History 38 (2013), 423-55.