The St Albans Pageant (1907)

The St Albans pageant of 1907 took place at the height of ‘pageant fever’ in Edwardian England, and was in many respects a typical example of the genre. It took place outdoors, in Verulamium Park – the site of the old Roman city, at this time in the private hands of the earl of Verulam but later a public park – and depicted eight scenes of local history, beginning with Julius Caesar and ending with a visit by Elizabeth I in 1572. Figures of national importance such as Caesar and Elizabeth, as well as Richard II and King Offa, among others, were portrayed, along with many other figures with a closer connection to St Albans, such as St Alban himself and the Bacon family of nearby Gorhambury House. With its Roman origins, and long and important monastic history, as well as being the site of England’s first martyrdom, St Albans was not short of episodes to depict in a historical pageant. The pageant had a cast of 3000 who performed six times in front of a grandstand with a capacity of 4000, and – as was typically the case – many local people served on organising committees or supported the pageant in other ways, notably by making the costumes for the large cast.

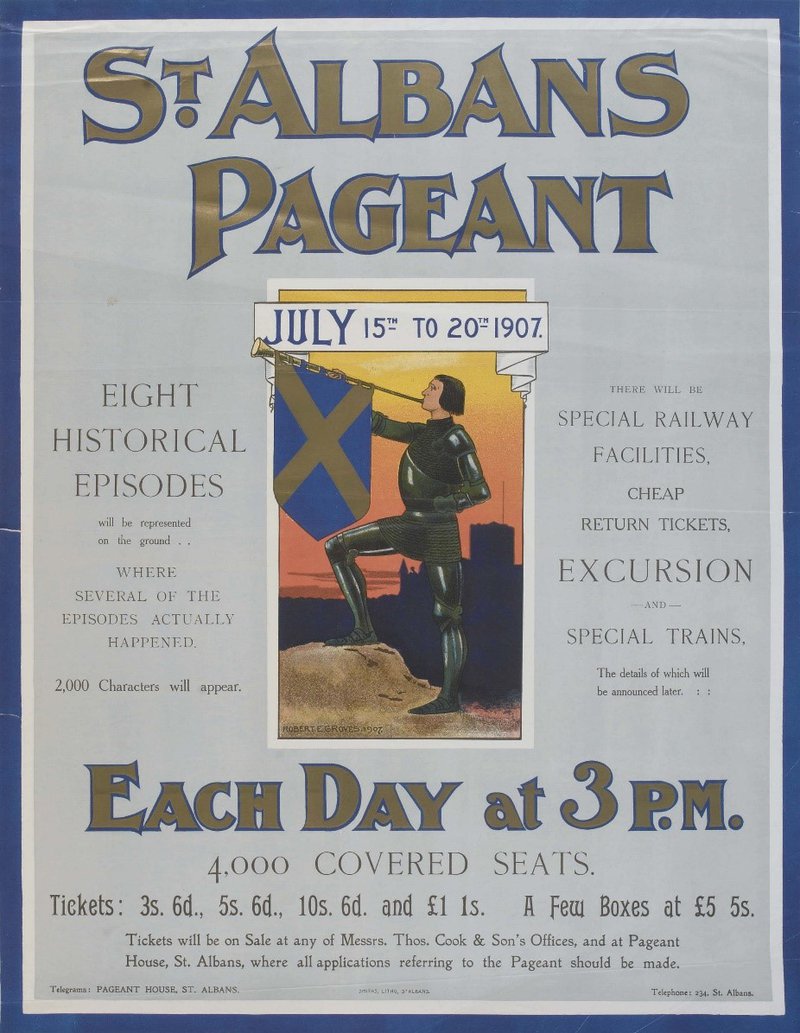

Above: poster advertising the 1907 St Albans

pageant.

Image courtesy of St Albans Museums.

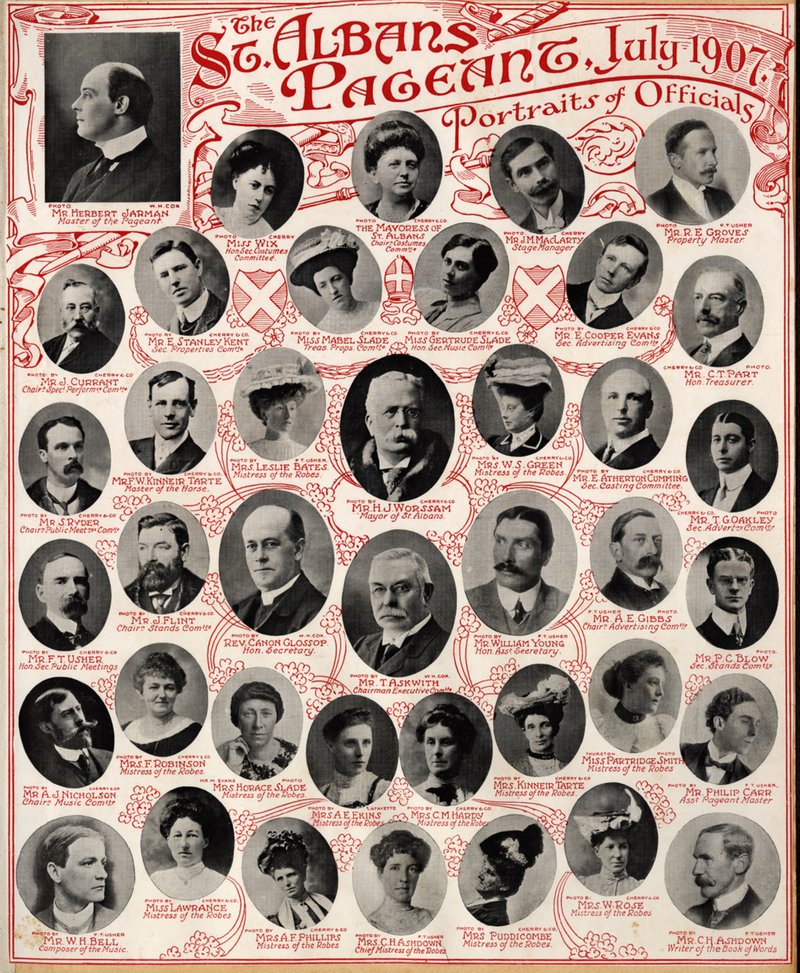

The pageant-master was Herbert Jarman (1871-1919), recruited from the Lyric Theatre in London and paid a substantial fee of £380. The script was by Charles H. Ashdown, who was a science master at St Albans School and secretary of the St Albans and Hertfordshire Architectural and Archaeological Society, as well as a published local historian. Ashdown’s wife Emily, a noted historian of costume, was ‘Chief Mistress of the Robes’; the costumes and props were created by Robert E. Groves, headmaster of the St Albans School of Art; and the music was composed by W.H. Bell, who lived in St Albans and was a professor at the Royal Academy of Music. Although the 200-strong choir was ‘entirely local’, as were the 30 members of the string section of the orchester, the wind players came from the London Symphony Orchestra. A large committee was established to organise the pageant, along with ten sub-committees including one to assist with the costumes and another to organise the horses that were used in this pageant, as in many others. A large number of prominent, mostly local, individuals agreed to act as guarantors against financial loss. The organisation centred on a building known as ‘Pageant House’ The dates of the pageant were 15 to 20 July. Special trains were laid on from London, and visitors came from as far afield as America, according to one local historian; certainly the American press had reported the preparations for the pageant.

Above: poster showing prominent individuals

involved in organising the 1907 St Albans pageant.

Image courtesy of St Albans Museums.

These preparations generated numerous small disagreements and discontents, and some larger ones, which were detailed in the regular ‘Pageant Gossip’ column of the Herts Advertiser in the run-up to the event. At various times it was reported that there was a shortage of male volunteers for the crowd scenes in the pageant; that there was a misapprehension that the working-class population of the city would be ‘locked out’ during pageant week; and in early June that there were rumours that the pageant would not be ready in time. Concern about possible damage to the Roman walls in Verulamium Park by the large crowds resulted in a large fence being constructed to protect them. Other criticism centred on the provision of alcoholic drinks at the pageant, which the Herts Advertiser saw as unhelpful: the author of ‘Pageant Gossip’ wearily explained that there would be a caterer, who would doubtless sell alcoholic refreshment, but this unsurprising and inconsequential fact had been ‘twisted into a charge of promoting drinking-booths; by the rumour-mongers. As the ‘Gossip’ author remarked,

It is surprising how many opportunities a great scheme like a Pageant provides for chronic grumblers. I heard the other day of one who had taken terrible offence because his offer to perform a part had not been accepted by return of post. From henceforth the Pageant is to lose his valuable services.

Other ‘grumbles’ came from letter-writers. One of the financial guarantors wrote anxiously in April, complaining that the pageant was not being well enough advertised at railway stations. Another correspondent, ‘One Interested’, stoked local rivalries: he or she had heard that episode 3, the martyrdom of St Alban, had been offered to performers from Radlett, and felt that, as the martyrdom took place very near the site of the pageant, it should be St Albans people themselves who enacted it. This echoed ‘criticism in the press’ about Berkhamsted people enacting a scene, but at the same time it was noted that other towns had not taken up the chance of performing: ‘Watford and Hertford are singularly coy. The spirit is willing but the flesh is weak, and there appears to be a possibility that they will dally too long and lose an opportunity which, in later days, they may regret.’ Hertford had been asked to supply men for the Lancastrian army in episode 7, but did not do so. (The prediction that they would regret this may not have been too wide of the mark, as Hertford staged its own pageant, also written by Charles Ashdown, a few years later in 1914.) Meanwhile, the pageant as a whole was being anxiously compared with the impending pageants at Oxford and Bury St Edmunds.

Costume-makers in ‘Pageant House’, St

Albans, 1907.

Image courtesy of St Albans Museums.

The organisers did not need to worry. The St Albans pageant went ahead, with large audiences, and seems to have been very successful, helped by the good weather. The atmosphere of the city changed during pageant week. Even those who did not have the substantial sum of 3s.6d. to watch the pageant (this was the lowest price for a seat in the grandstand) could experience the pageant for free. Many years later in 1962, the mayor of St Albans Elsie Toms, who had lived in the city as a child at the time of the 1907 pageant, remembered:

There were many amusing and incongruous sights in the streets. Since there were no extensive dressing-rooms on the site for the very large cast, the performers dressed at home and walked or drove to the pageant ground, and one laughed to see a Roman soldier strolling along smoking a pipe, and a Briton in skins riding a bicycle. One saw an Elizabethan lady in brocade (probably the drawing-room curtains cut up), walking arm-in-arm with a cross-gartered Saxon in a yellow wig and long drooping moustache. It all added to the fun, and it brought trade to the shops and warmed the hearts of the shopkeepers. The ordinary citizen began to comprehend that was something special about his city and something worth preserving. It was little enough, but it was the beginning of civic knowledge which leads to civic pride.

Toms’s remarks about ‘civic pride’ and citizenship echoed the themes of the pageant that were repeatedly emphasised by the organisers and in the local press, in which phrases such as ‘local patriotism’ and ‘patriotic citizen’ were scattered. The ‘educative influence of the pageant’ was an important theme. In the souvenir programme, the dean of St Albans, W.J. Lawrance, made it clear that the pageant was as much about stimulating local citizens to work for the common good in the present as it was about commemorating the past. He emphasised

the transcendent claims of St Albans to the deep and abiding interest of all those who value the great story of our National History, our National Christianity, and National Liberties, in which the place has has played so conspicuous a part; and who are inspired thereby to hand that story on to those who shall come after them, as a treasured and living memory – inciting them, not to a mere glorying in an illustrious past, but to emulate in widely differing circumstances, the spirit of the achievements of their forefathers.

Thus some of the scenes featured moments at which St Albans had played an important part in the ‘National History’, including the peasants’ revolt and the Wars of the Roses, while others depicted royal visitors – alive in the case of King Offa and Elizabeth I, dead in the case of queen Eleanor, wife of Edward I. (St Albans was the site of an Eleanor Cross, which was dismantled in the eighteenth century.)

Souvenir postcard (based on a specially commissioned watercolour) depicting episode 5, the funeral procession of Queen Eleanor. Image courtesy of St Albans and Hertfordshire Architectural and Archaeological Society.

The pageant had a

clearly articulated educational function, demonstrated in the historical notes

that accompanied each episode in the souvenir programme. Thus not only was episode

5, ‘The Eleanor Procession’, a sombre and impressive scene in the pageant, but

it also made a historical point:

The

historic value of this Episode is that it shows the precise organisation of the

mediaeval services which were designed to meet every emergency, and not left to

the chance vagaries of individual ecclesiastics. It also shows the ways in

which the monastic hospitality supplied the place of the modern hotel – without

handing a bill to the guests. The cellarer’s accounts of different monasteries

go to show that the monks were abstemious in what they ate and drank

themselves, but generous, if not luxurious, in the entertainment of their

guests. The popular songs and pictures of bon

vivants, wearing monkish habits, are not true to history.

It is possible that this message was lost on most of those who saw the

pageant, especially if they could not afford a shilling for the programme on

top of admission to the pageant (the book of words had to be purchased

separately, adding further the cost of attendance). Other attempts to engage

the population of the city in more scholarly historical pursuits at the time of

the pageant were not successful: a lecture on the battles of St Albans, for

example, one of which was portrayed in the pageant, attracted only a ‘moderate

attendance’.

Yet the pageant as a

whole was held up as an example for others to follow. In some respects Jarman

and Ashdown out-Parkered Louis Napoleon Parker in their attention to locality,

authenticity and detail. The novelist and journalist Robert Barr, writing in

the Idler – in an article for which

the St Albans pageant committee provided the illustrations – praised most

aspects of the organisation of the pageant: ‘In a pageant we want to see the

people who belong to the place doing the best they can, and thus rest ourselves

from the historical accuracy of [the actor and theatre impressario] Mr [Herbert]

Beerbohm Tree’. Although Barr was not happy about the use of members of a

London-based orchestra, on the whole he judged that the St Albans pageant ‘has

originated in the way that I have recommended’, and praised the involvement of

local men such as Ashdown, Groves and Bell, ‘a native of St Albans’. It was, he

considered, a community effort worthy of great praise. It was certainly hard

work: in 1920 the assistant secretary William Young remembered that ‘[t]he

stiffest job I ever had was in connection with the St Albans Pageant ... It was

like running a huge business in addition to one’s own private concern’. The

work did not end with pageant itself: Young recalled that it ‘took months to

wind up, and to get the accounts in order’. Eventually these accounts showed an

excellent profit: £760 according to Young, although the draft accounts showed £668. 11s.9d. Most of the profits were

divided between the Hertfordshire County Museum (Iater called the Museum of St

Albans) and the St Albans Hospital, with a smaller sum going to the Mid-Herts

Infirmary, also located in St Albans.

Above: a member of Boudica’s entourage, as seen in the St Albans pageant of 1907. Image courtesy of St Albans Museums.

Despite the obvious success of the 1907

pageant, St Albans did not stage another until 1948. There was, however, a

one-off ‘pageant’ in 1909, held in Clarence Park, to commemorate the entente cordiale between Britain and

France. A delegation of 43 visitors from Caen in Normandy, home town of the

greatest Norman abbot of St Albans, were treated to a children’s pageant, again

accompanied by music written by Professor W.H. Bell. This appears to have been

a series of tableaux depicting the four nations of Britain, and involved an

impressive 2500 children. Various other events, including a mayoral banquet and

a display of sports, were held, and a memorial window – known as the entente cordiale window – was unveiled

in the cathedral. Another event billed as a Rotary Club ‘pageant’ took place in

Verulamium Park in 1933. This was really more of a fair or fete, accompanied by

an open-air service on what was referred to as the ‘Old Pageant Field’. The

highlight was a reconstruction of the attack on Zeebrugge in 1918, using

minature boats on the newly constructed lake in the park. Some of the men

involved in the actual raid took part in the ‘reproduction’.

As Robert Barr had emphasised, the St Albans

pageant was in many ways a classic of the genre, although neither of the two

most prominent pageant-masters of the Edwardian period – Louis Napoleon Parker

or Frank Lascelles – were associated with it. It lived for a long time in the

memory of the city: for example, the St

Albans Review published recollections of the pageant 70 years later in

1977. One writer noted that it seemed remarkable, in the age of television,

that so much had been done without the aid of microphones and loudspeakers. The

pageant was widely praised and happily remembered – and these memories lasted

well into the second half of the twentieth century.

For more details of the 1907 pageant, see the database entry here. See also Mark Freeman, ‘“Splendid Display; Pompous Spectacle”: Historical Pageants in Twentieth-Century Britain’, Social History 38 (2013), 423-55