Here be Dragons, or Strange News out of Essex: (More) Giant Lizards at the Pageant!

Last December I wrote about Egbert the sixty-foot fire-breathing dinosaur, a sixty-foot, ‘as large as a church’, who stole the show at the Birmingham Pageant of 1938. Other pageants included dinosaurs in scenes such as St. Wilfred’s in Sussex (1965) to commemorate the discovery of the first positively identified dinosaur fossils nearby in the 1820s.

Many pageants included dragons, proving that Historical Pageants are at least as cool as Game of Thrones (probably more). Many of these appeared in (often comic) recreations of St. George’s battle with the dragon as in Hampton (1929), Basingstoke (1951). There are also many dragons which are integral parts of the narrative, blending history and mythological folklore. At Bignor (1912), an ancient Briton village is attacked by a nine-foot black dragon which is eventually killed to much rejoicing. In the Forfarshire Women’s Institute Pageant (1930), a slightly inept farmer sends each of his nine daughters in turn to fetch water, only for them to be eaten by a dragon. Martin, the lover of one of them, eventually manages to kill the dragon.

A Reconciled St George and the Dragon from an amateur silent film of the Pageant of Basingstoke (1951) held in Hampshire Archives and Local Studies.

The Salisbury Peace Pageant (1919) features a thirteenth-century scene with an ecclesiastical procession. Dragon-beaters were employed (obviously) to keep the errant beast in check. Clergymen were clearly the most effective against dragons, with Bishop Jocelin managing to free captured children from one in the Wells Pageant (1923). The book of words notes that the scene is symbolical of holiness and courage overcoming evil of immense magnitude. Likewise, in the Oxford Historical Pageant (1907), the dragon is largely symbolic, in which a knight rescues a damsel, Knowledge from the dragon called Ignorance by discarding his weapons in favour of a scholar’s cap and gown.

In the Swansea Pageant (1935) the Red Dragon was taken as a symbol of the nation, attacked by English knights: though, as the press described, ‘the Red Dragon of Wales’ was not ‘subdued’. In this latter episode, Welsh knights united, and their cloaks flashed back ‘amid smoke and flames to unite in a fiery dragon’.[1] In a later scene depicting Owain Glyndwr’s rebellion the dragon writhed ‘about the stage’.

My favourite Here Be Dragons scene features in the Pageant of Saffron Walden (1910), which featured a scene on the ‘Flying Serpent of Walden’. It is safe to say that the writers of the pageant struggled for material: the London Daily News admitted that the town ‘does not possess the moving records of Colchester, or even of the old town of Maldon, but its history extends from the time of Edward the Confessor.’[2] In 1669 (nine years after the Royal Society was founded), the whole town and district was thrown into alarm due to the appearance of a ‘Flying Serpent…whose awesomeness was beholded of the most respectable inhabitants and whose further excursions and advances were the subject of most lively apprehension on the part of our townsfolk.’[3] The book of words explained that the town was ‘particularly prone to dragons’.

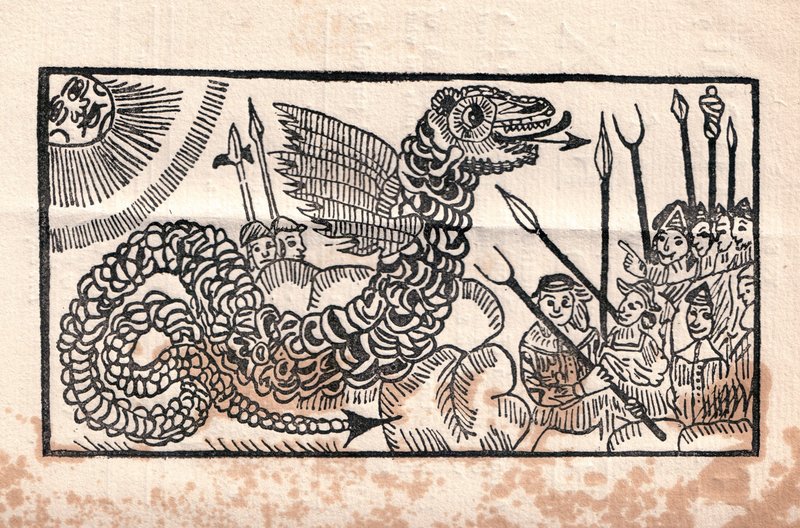

The town, which was for many years twinned with the village Gullible in the Netherlands, was thrown into turmoil and confusion after a Gentleman out riding late reported that his horse had been assailed by this serpent and which now feared was worrying the cattle in the neighbourhood. Not long after this, two men came across the Serpent lying (or sunbathing) on the hillside, the smallest part of him being about ‘the bigness of a Man’s Leg, ‘on the middle as big as a Man’s Thigh, his eyes were very large and piercing, about the bigness of a Sheeps eye, in his mouth he had two row of Teeth which appeared to their sight very White and sharp, and on his back he had two wings indifferent large’. Heavily-armed search parties were sent out to kill the dragon, though unfortunately ‘now upon the sight of a man, it presently betakes its self to the Wood, where he remains safe, none daring to come nigh it with Clubs’.[4]

From The Flying Serpent, or,Strange News Out Essex (1669)

Dragons in pageants could be used to depict a number of things such as the English nation and its (Turkish), religion, knowledge, and Patron Saint or the resilience of Welsh nationalism. At other times, the dragon was a depiction of the weird and wonderful folklore of a town.

[1] ‘Swansea’s Great Pageant’, 7.

[2] London Daily News, 25 May 1910, 4.

[3] Scenes from Old Walden (Saffron Walden 1910).

[4] All quotes from Richard Jackson, Thomas Presland and John Knight, ‘THE Flying Serpent, OR, Strange News out of ESSEX’ (1669).