How (Not) to Run a Pageant in six easy steps!

Edward P. Genn, Pageant Master for the Wakefield Historical Pageant (1933), declared in a promotional article that ‘If you want to go into an uncrowded profession try that of Pageant-Master! There are only three practising in this country, and as historical and industrial pageants are yearly increasing in popularity there is no competition and we are fully engaged and booked up years in advance, so there is a considerable amount of room for anyone who enjoys being worried by thousands of people six months of the year.’ Genn warned, however, that the Pageant Master was a ‘King of Beggars’ in enlisting so many people to work voluntarily, recruiting the fattest man in Manchester for the Manchester cotton pageant: out of 300 who applied, the winner was 25 stone! Genn suggested that ‘The main points for success are the following: a cool head under any conditions and a sense of humour and patience. If you have these qualities you may safely embark on one of the most interesting professions possible in the world.’

This set me musing on the lost art of Pageant Mastery. There are quite a few manuals to organizing pageants, including Mary Kelly’s How to Make a Pageant (1936) and Anthony Parker’s Pageants: Their Presentation and Production (1954). The latter outlined over twenty-five different groups of performers, organizers and committees that the budding pageant master would have. Parker based most of his examples on the 1953 Warwickshire Coronation Pageant, a spectacular completely over-the-top event, referred to as ‘Hollywood-in-Warwickshire scale’, which was to feature 3000 performers, a large choir, 150 horses, a pack of stag-hounds, a flock of sheep, and ‘a balloon ascent’. Despite being attended by over 42000 people, the pageant lost £6350 (around £160000 today). It seemed that there were a myriad of things that could go wrong.

Above: Anthony Parker offering advice to performers at the Warwickshire Coronation Pageant (1953), Plate from Pageants: Their Presentation and Production (1954)

Therefore, drawn from my work on hundreds of pageants, I drawn up a few do’s, and mainly don’ts:

1. Get Permission to Hold the Pageant!

Genn’s Wakefield pageant was almost scuppered at the last minute when the local Parks Committee refused to allow the Thornes Park to be closed to the public during the pageant. Obviously, this would make ticketing impossible and ensure the Pageant was a failure. The impasse was only resolved less than two weeks before the pageant opened, with the Town Clerk writing a pleading letter that the failure of the Pageant ‘would be a disaster not only to our Guarantors [£2500 had been raised by local townspeople], but to the Corporation and every citizen of Wakefield.’ Tentative plans for the Sevenoaks Pageant for the 1951 Festival of Britain were dashed when the National Trust, which had recently taken over Knole Park, refused to forgo a week of admissions required if the pageant were held there, leading the council to cancel the event.

2. Don't Antagonise Local Newspapers

The Pageant committee for the 1947 Bradford Centenary Pageant made the fatal mistake of hiring using Printers from out of town, instead of the local publishers, which was unfortunately owned by the same company as the local newspaper. This created a scandal which led to a number of the Pageant’s executive committee resigning either in protest or in apology, with one former member publically airing their grievances in the pages of the Bradford Argus:

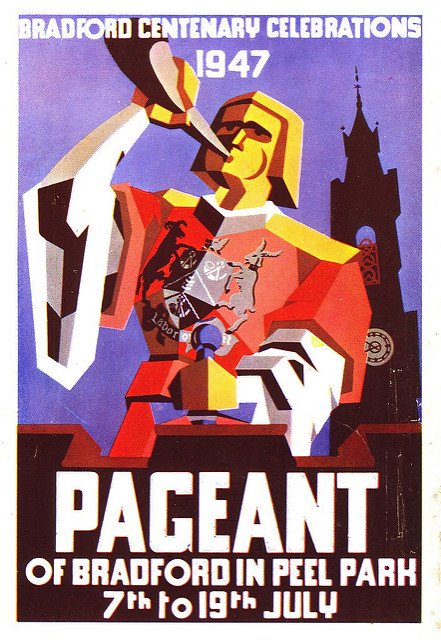

It is a positive disgrace that advertising specialists who pay hundreds of pounds in rent and rates should have their offers ignored…And what of Bradford printers? Are they not capable of producing this for the city?...Yet they do not get a smell of a job for their own city; they are denied the opportunity of letting our citizens examine the really high-class work which they can produce’. The newspaper went on to wage a continued vendetta against every aspect of the pageant, including the design of the promotional poster, ‘detestable modern cubism’. The Bradford Pageant was a terrible failure, with only 300 people attending the first performance, losing over £13000!

'I think that the man on the poster in question looks as though he had just had a bad fall down a steep hill covered with flints.’ The Offending Poster for the Bradford Centenary Pageant (1947), source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/bradford_timeline/7567360922/in/album-72157630569897298/

3. Don’t Mock the Town

This may seem pretty obvious, but it’s worth repeating: townspeople can be surprisingly sensitive and are unlikely to take jokes at their own expense. So long as a pageant was favourable to the town (and slighting to its nearby rivals), people were generally appreciative no matter how weird: the Deal Pageant (1949) was narrated by the Devil in conversation with a damned Anglo-Saxon Earl, who extolled the virtues of the town’s natural harbour! Clement Jones, the theatre critic for the Wolverhampton Express and Star objected to a number of scenes from the Wolverhampton Centenary Pageant (1948) labelling it as mere ‘burlesque’ and ‘fifth-rate touring music hall stuff’, and expressing ‘grave doubts about its artistic value’ and that the Pageant lacked the ‘Spirit of the Town’. Several episodes most raised his ire, including a song in one episode ‘Water Is Not Everybody’s Beverage’, in which drunken residents extolled the virtues of beer in favour of Wolverhampton’s dubious water-quality. Worse still, a subsequent scene showed Bailiffs confiscating policemen’s tunics, the town’s fire-engine, and the Mayor’s robes for an unpaid debt. A later scene showed the a history of policing (with no obvious link to the town), featuring a risqué portrayal of a current-day policewoman, as well as a futuristic scene with ‘spivs’ and their girlfriends dancing to a traffic light, presided over by futuristic a robot policeman! This predictably went down poorly with locals who stayed away or else wrote hostile letters to local newspapers.

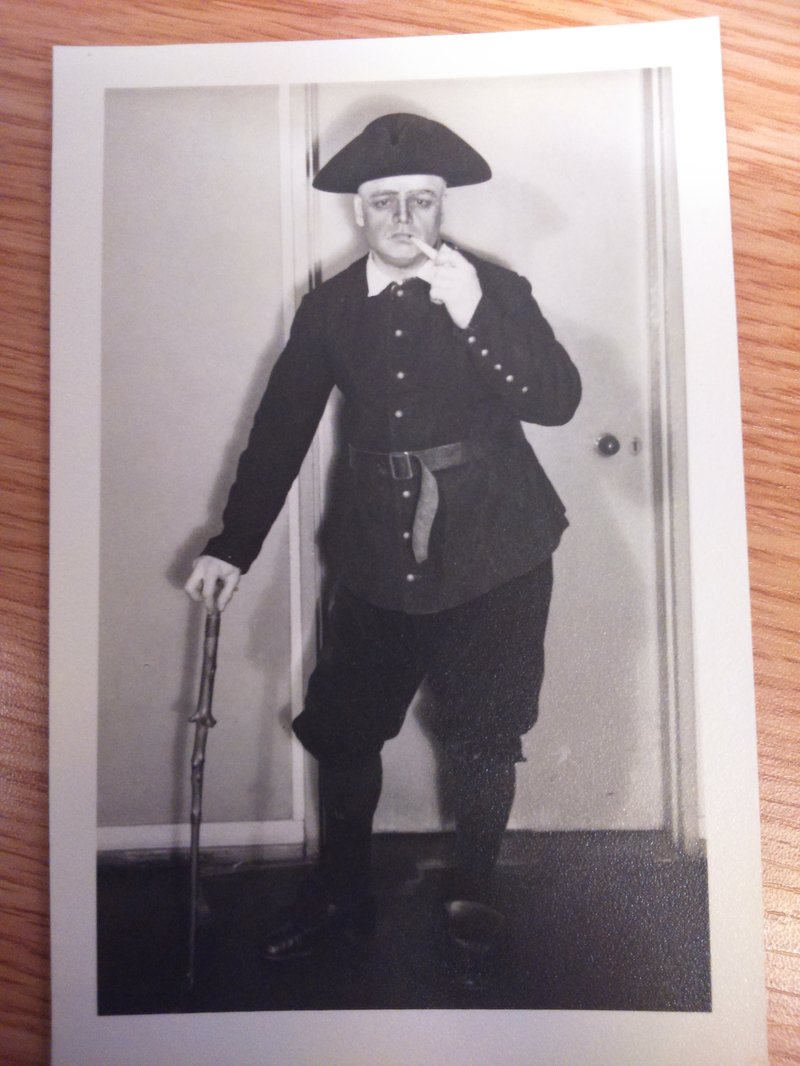

The Mayor H.E. Lane dressed as his predecessor in the Wolverhampton Centenary Pageant (1948),Photograph in Wolverhampton City Archives, Reference DW-31/2

4. Don’t expect that strangers will be interested in your town’s history

Despite some heavy rain at Bristol’s Cradle of Empire pageant of 1924 (see below), along with less than hoped for audiences and fears of pickpockets (who preyed on many a pageant-goer), and the sudden death of the producer and author Charles Latham, it seemed that the pageant would be a limited success, losing a small amount of money. Unfortunately, the great Pageant Master, Frank Lascelles, convinced the organisers to restage the pageant at Wembley rena for a week. Lascelles hoped that Bristol’s pageant, with its story of the city’s place in the British Empire, from John Cabot’s discovery of Newfoundland through to the departure of William Dampier on his way to discover Australia, would provide a welcome prelude to the much grander Pageant of Empire which Lascelles was also organising. And thus, 2000 performers took the train between Bristol and London daily. Sadly, few of the hundreds of thousands who visited the Festival of Empire each day wanted to pay extra to visit the pageant. Despite early use of microphone amplification, the dialogue of the pageant was completely lost among the cavernous empty seats of the Stadium, at which only one or two thousand witnessed the pageant. As the Times judged, ‘The Bristol Pageant deserved more support than it gained; but, amid such a wealth of competition of different kinds, there was perhaps too much attention in expecting the vast spaces of the Stadium to be filled for a local enterprise’. It was estimated that against £20000 spent on relocating the pageant to Wembley, only a few hundred pounds had been made. Overall, the pageant lost over £13000, though undeterred Bristol continued to hold pageants in 1930, 1943, 1946 and 1949. The conclusion drawn from Bristol, and a number of other towns which banked upon tens of thousands of visitors travelling great distances, must be that however much one values one’s local history, others might not be so interested.

5. Make sure that the Pageant mentions the town

The issue of what to do in a city such as Birmingham, which had rapidly grown from a few small hamlets into Britain’s second city in the space of a couple of centuries, perplexed the organisers of Birmingham’s Centenary Pageant of 1938. This was exacerbated because the city, suffering a prolonged period of industrial depression, was unlikely to warm to a pageant celebrating it’s glorious past when it actually made things. The result, staged by the pageant master (or mistress), Gwen Lally, chose the unprecedented decision to include as two of the largest scenes episodes with no ostensible links to Birmingham. The first episode ‘the Dawn of History’, depicted British history from the time of dinosaurs (anachronistically living and fighting cavemen) through to the Norman Conquest. Whilst the two thirty-foot fire-breathing dinosaurs have subsequently become part of urban legend, they very clearly had nothing whatsoever to do with Birmingham, leading the Leamington Spa Courier to refer to the episode as ‘a daring overture, especially as the introduction of such monsters gives a quite erroneous impression that the pageant is intended to be a burlesque.’ The other great scene splendidly re-enacted the Battle of Crecy, fought in France during the hundred years’ war, with thousands of knights and archers with the claim – tenuous at best – that some of the English soldiers had come from villages in the area. Other scenes, depicting the destruction of the radical philosopher Joseph Priestley’s house by a mob in 1791 and the defence of Aston Hall by heroic Royalist soldiers against villainous Parliamentarians prompted stern criticism from the Manchester Guardian: ‘The view of history which it presents is not everybody’s view…In particular, it is not the view of the Liberal or the democrat or the upholder of the British Parliamentary tradition; but it is a picturesque view and it makes a handsome pageant.’ A distinct apathy from working class areas of the city, rain and a cancelled royal visit conspired to see the pageant make a significant loss of nearly £12000.

6. Gauge Local Enthusiasm

Gwen Lally was one of the most prolific Pageant Masters and despite a number of successes, she also encountered several failures. The Battle Abbey Pageant of 1932 sought to recruit 7000 performers from across Sussex for a pageant which only featured Battle Abbey and its town. Many of the performers would have to travel significant distances by train or bus to each of the sixteen performances as well as a number of rehearsals, forgoing pay. Predictably, the other towns in the area proved supremely unwilling. By February 1932, Hastings had recruited a grand total of 8 people for the smuggling scene. In March, the Mayor of Rye formally abandoned his town’s episode ‘several unsuccessful attempts to obtain volunteers’, and resigned from the pageant committee. Whilst a few members from local towns did perform, the Mayors and local authorities all pulled out and by the end of May only 1500 out of 7000 had signed up, leading to one local wag suggesting that a single mourner could be employed for one scene, doubling as the corpse, and that ‘One drunken smuggler complete with rum bottle, might, in the capacity of a Preventive Officer, arrest himself.’ Despite the drafting of enthusiastic schoolchildren – who at one point almost defeated the Normans at the Battle of Hastings! – the lack of performers and enthusiasm showed, with an irate newspaper critic complaining that ‘I have found that a large number of people really enjoyed it, but always found that these people had never seen a pageant before.’ A number of pageants woefully misjudged local enthusiasm and consequently performed to empty seats as people preferred to stay home.

Next week I will be writing about the bane of all Pageants, something which no pageant master could prepare for: the Great British weather!